This article will overview variables and scopes in JavaScript and other related things.

Global Scope.

Let's declare var and let variables in our JS file.

If variables are not in the function, like in the example below, they become a part of Global Scope.

var a = 10;let b = 10;This is bad for a few reasons.

Reason one: a lifetime of variables in Global Scope is infinite until a user closes the tab in the browser. If you store a lot of data in Global Scope, it may affect performance and memory consumption.

Reason two: declaring a variable in Global Scope without a good reason is an efficient way to write poor code, because the code written this way is harder to support, test, and understand.

Reason three (for var only): If you are not using 'strict mode' in your JS file, var in Global Scope will become the property of the window object. With this, you can accidentally overwrite the window’s object variable or function, and that would lead only to pain, fear, and bugs.

Function Scope.

var variable behaves differently than let and const when declared in the function.

function outer() { var x = 12; function inner() { console.log(x); // 12 } if (2 + 2 == 4) { console.log(x); // 12 } inner();}outer();As you can see, we can access the x variable anywhere in the function where it was declared. Independent of nesting level. In that case, the x variable lifetime ends only with a closing bracket of function where it was declared.

Block Scope.

Opposite of Function Scope is the Block Scope. When you declare a let variable, its lifetime ends with a closing bracket of its block.

{ let x = 10;} // lifetime of x ends.Also, you can access the x variable only from inside the block where it was declared.

function func() { if (2 + 2 == 4) { let x = 10; console.log(x); // 10 } console.log(x); // Uncaught ReferenceError: x is not defined}func();const Variable.

const is the same as let, but you can't change the variable value after initialization.

const x = 10;x = 5; // Uncaught TypeError: Assignment to constant variable.

Temporal Dead Zone (TDZ)

And this is where all the fun begins.

function simpleFunc() { console.log(x); // Reference error let x = 10;}simpleFunc();And what is going to happen if we change let to var?

function simpleFunc() { console.log(x); // undefined var x = 10;}simpleFunc();Interesting. To understand this, we need to talk about hoisting.

Hoisting is JavaScript's mechanism that moves variables and function declarations to the top of their scope. And if you try to use a variable before it was declared in the code, you will get an undefined value or the reference error depending on which variable you try to access var or let.

JavaScript binds a variable or a function to its scope that way.

Note that only variable declaration pops up, not the variable initialization!

So what is TDZ?

TDZ is the term to describe a state when a variable/function is unreachable. Like in the example above, we can't access the x variable before it was declared because console.log(x) is in Temporal Dead Zone.

Also, var and let/const behaviors are different in TDZ. In the case of let/const, you would get a Reference Error while trying to access a variable in TDZ. In the case of var, you get undefined, which may lead to problems.

Arguments in functions & Lexical Environment.

Arguments that you pass into the function are attached to the scope of that function.

function func(x) { console.log(x); // undefined}var x = 'I'm outside the function!';func();Wow! We get undefined here! The reason is we don't pass a value to func() when calling it, but in the function declaration, func(x) has x as the argument. So when JavaScript calls console.log(x), it finds the x variable in the function's scope. But since we don't pass any value as an argument, the value of x is undefined.

Let's change the example a bit.

function func(a) { console.log(x); // I'm outside the function!}var x = 'I'm outside the function!';func();So in this example, JavaScript does the next thing, it searches for the x variable in the function's scope and doesn't find it. Then JavaScript moves to the outer scope and searches for the x variable there, and now JavaScript finds it and passes the value of the x to the console.log();

When JavaScript looks for a variable, it starts from the local scope and moves to outer scopes until it reaches the Global Scope. If JavaScript did not find a variable in Global Scope, you would get a Reference Error.

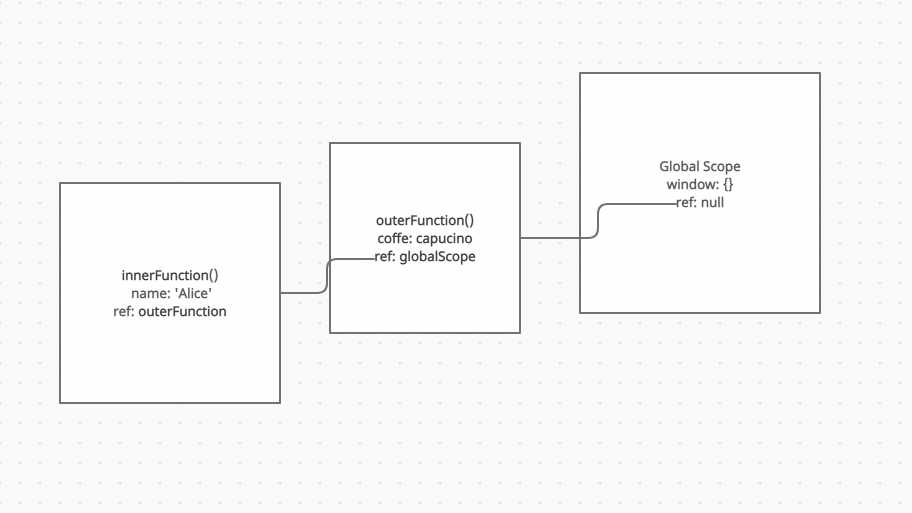

This mechanism is called the Lexical Environment. To easily understand how it works, imagine when you create a function and declare a variable in it. JavaScript creates the object for this function, containing all functions, variables, and ref to an outer object. When you try to access a variable and JavaScript does not find it in the current Lexical Environment, the JavaScript goes to the outer Lexical Environment by the ref.

This diagram shows Lexical Environment conditionally but can help you understand this.

In this diagram, coffee and name are variables in functions lexical environment, and ref leads to outer Lexical environment. Ref of Global Scope is null.

Closures.

Imagine we want to create a function that counts how much ice latte we have drunk. But there is one condition, we want to make the counter variable accessible only within the function.

function drinkLatte() { let counter = 0; return ++counter;}console.log(drinkLatte()); // 1console.log(drinkLatte()); // 1console.log(drinkLatte()); // 1Have you noticed the issue? Is the counter variable accessible only with the function? Yes. Does this code work properly? No.

Every time we call drinkLatte(), it will return 1. It works because the counter’s variable lifetime ends with the function’s close bracket. So in this example, we create a counter variable three times with a value of 0, then increment the counter to a value of 1 and return. We need a mechanism that can save the state of variables.

Closures can help us with that. Here is another example of using closures.

function getLatte() { let counter = 0; return function drinkLatte() { return ++counter; };}const latte = getLatte();console.log(latte()); // 1console.log(latte()); // 2console.log(latte()); // 3It works! We created a new function named getLatte which wrapped our previous function. The getLatte function has a counter variable declared in it, and it returns the drinkLatte function, which increments the counter variable from the outer function.

Then we initialize the latte variable with returned function, so now we can call the drinkLatte function from that variable.

With Closures, we can expand the lifetime of a variable and use it in inner functions.

Conclusion.

Avoid using Global Variables without good reason.

Use let & const instead of var as it is much safer.

Be aware of TDZ and keep in mind how Lexical Environment works.

That’s all! Thanks for reading. If you liked the article, you could help Ukraine. Even $1 would help.

Come Back Alive Fund: https://savelife.in.ua/en/donate-en/.